Corresponding author: Yuka Koike, yukkoike@bri.niigata-u.ac.jp

DOI: 10.31662/jmaj.2024-0038

Received: March 1, 2024

Accepted: March 14, 2024

Advance Publication: June 17, 2024

Published: July 16, 2024

Cite this article as:

Koike Y. Abnormal Splicing Events due to Loss of Nuclear Function of TDP-43: Pathophysiology and Perspectives. JMA J. 2024;7(3):313-318.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are neurodegenerative diseases with a progressive and fatal course. They are often comorbid and share the same molecular spectrum. Their key pathological features are the formation of the aggregation of TDP-43, an RNA-binding protein, in the cytoplasm and its depletion from the nucleus in the central nervous system. In the nucleus, TDP-43 regulates several aspects of RNA metabolism, ranging from RNA transcription and alternative splicing to RNA transport. Suppressing the aberrant splicing events during RNA processing is one of the significant functions of TDP-43. This function is impaired when TDP-43 becomes depleted from the nucleus. Several critical cryptic splicing targets of TDP-43 have recently emerged, such as STMN2, UNC13A, and others. UNC13A is an important ALS/FTD risk gene, and the genetic variations, single nucleotide polymorphisms, cause disease via the increased susceptibility for cryptic exon inclusion under the TDP-43 dysfunction. Moreover, TDP-43 has an autoregulatory mechanism that regulates the splicing of its mRNA (TARDBP mRNA) in the healthy state. This study provides recent findings on the splicing regulatory function of TDP-43 and discusses the prospects of using these aberrant splicing events as efficient biomarkers.

Key words: ALS/FTD, TDP-43, Loss of function, Cryptic exon, TDP-43 autoregulatory mechanism

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is an adult-onset neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by motor neuron-specific degeneration, which causes progressive muscle weakness, fasciculation, and atrophy, leading to respiratory failure (1). Fifteen percent of patients with ALS have concomitant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with cognitive, behavioral, and language deficits (2).

After the discovery of TDP-43 pathology associated with both ALS and FTD in 2006, these two diseases are firmly placed on a spectrum with similar underlying molecular mechanisms (3), (4). TDP-43 is an RNA-binding protein encoded by the TARDBP gene generally localized in the nucleus (1), (2). In the nucleus, TDP-43 usually regulates multiple aspects of RNA processing, including pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) splicing (5). Nuclear depletion and cytoplasmic aggregation of TDP-43 are key pathological features in more than 97% of ALS cases and nearly 50% of cases with FTD (FTLD-TDP) (1), (2).

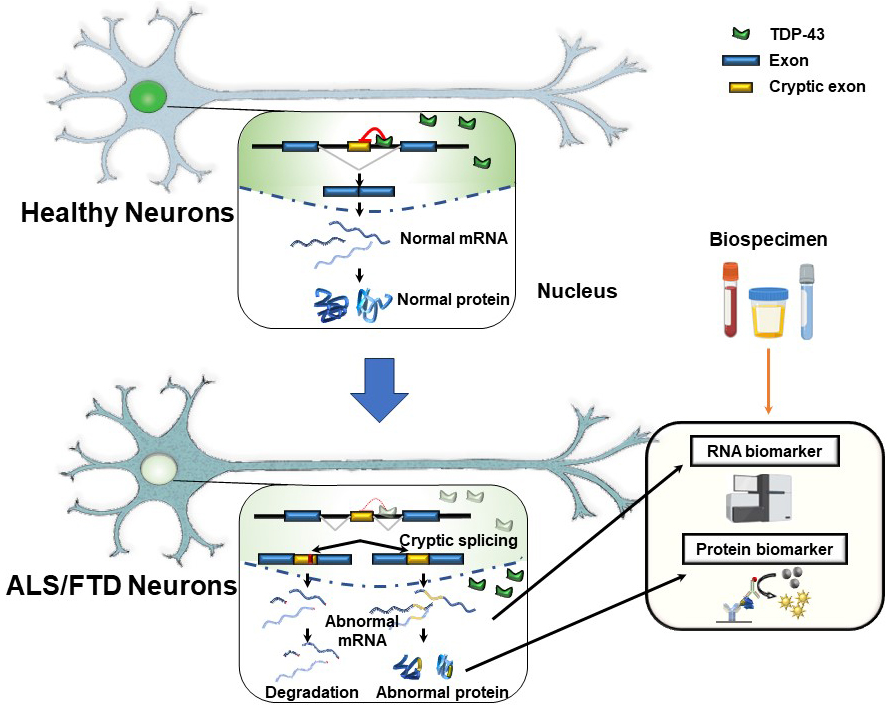

Suppressing cryptic exons during pre-mRNA splicing is one of the critical functions of TDP-43 in the nucleus (6), (7). Exons, which code for proteins, are spliced together in normal splicing, while introns, the intervening sequences, are spliced out. However, some genes have sequences within introns that mimic exons and can be incorrectly included in the mRNA. The “cryptic exons” can disrupt the reading frame of the proteins. Accordingly, including cryptic exons destabilizes the mRNAs, leading to their degradation or coding aberrant peptides. TDP-43 is crucial in inhibiting these cryptic exons from slipping into mRNAs. There are binding sites for TDP-43 around the cryptic exon sequences. When TDP-43 is functional in the nucleus, the cryptic exons are kept out of mRNA (Figure 1) (7), (8). However, when the TDP-43 function is depleted in the nucleus, these cryptic exons slip into the mRNAs of many different genes (7), (8). The discovery that TDP-43 represses cryptic exons provides exciting insights for explaining the molecular mechanisms underlying ALS and FTD. We can expect the development of disease-specific biomarkers and effective therapeutic targets based on the pathogenesis. However, it remains unclear which cryptic splicing events are critical for TDP-43 proteinopathy.

In 2019, two independent studies uncovered an important human cryptic splicing target of TDP-43―stathmin 2 (STMN2), which encodes a protein regulating microtubule stability in neurons (9), (10). RNA sequencing data from human neuronal cells with TDP-43 depleted were analyzed. The analysis found that the STMN2 gene harbors a cryptic exon (the so-called exon 2a) that is usually not included in mature STMN2 mRNA. Since the first intron of STMN2 contains a TDP-43 binding site, TDP-43 typically suppresses, including cryptic exon. When TDP-43 is depleted in the nucleus, exon 2a is incorporated into mature mRNA. This exon harbors a stop codon and a premature polyadenylation signal, producing truncated STMN2 mRNA (9), (10). Abnormal splicing variants and reduced STMN2 protein levels are significant features of familial and sporadic ALS cases with TDP-43 pathology. This cryptic splicing event in STMN2 represents critical neuronal impairments caused by TDP-43 dysfunction. Both teams found that upregulating STMN2 can rescue the defects of axonal regeneration due to TDP-43 depletion in human iPSC-derived neurons (9), (10). These facts indicate that the dysregulation of the STMN2 splicing partially causes TDP-43-dependent neurodegeneration. Moreover, STMN2 cryptic exon inclusion plays a role in the pathogenesis of FTD (11). Truncated STMN2 RNA is elevated in the postmortem brain tissues from FTLD-TDP-43 cases but not in controls or cases with progressive supranuclear palsy, a different neurodegenerative disease without TDP-43 pathology. Of interest, truncated STMN2 levels correlate with phosphorylated TDP-43 protein levels (11). We speculate that STMN2 cryptic exon inclusion may be prior to the formation of TDP-43 in the neurons, even without TDP-43 nuclear depletion. Thus, TDP-43-dependent cryptic splicing events in ALS and FTD may allow us to detect the earliest events of TDP-43 pathology. The breakthrough related to the STMN2 cryptic splicing event can provide a clue to explain the pathogenesis of TDP-43 proteinopathy.

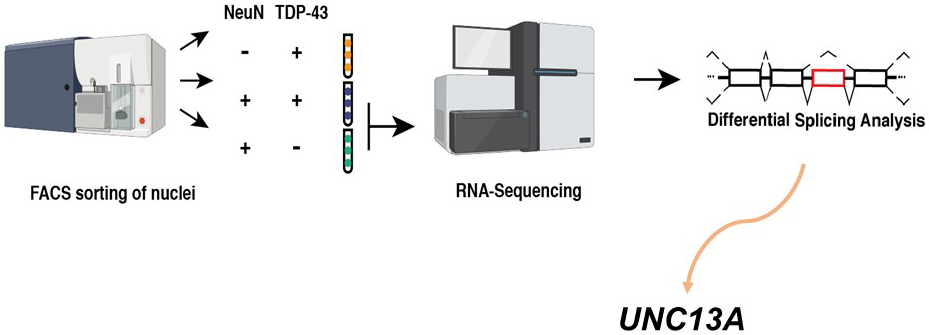

Our group and another recently identified multiple novel cryptic exon inclusion events due to the loss of TDP-43 functions in human neurons (12), (13). Our group reanalyzed valuable RNA sequencing data created by Dr. Edward Lee’s team (14). To identify changes associated with the loss of TDP-43 from the nucleus, they used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich neuronal nuclei, either with or without TDP-43. They then performed RNA sequencing to compare the transcriptomes between TDP-43+ and TDP-43- neuronal nuclei from the brains of FTD/ALS patients. As a result, they revealed a multitude of interesting differentially expressed genes (14). We reanalyze their data differently―searching for novel cryptic exon splicing events by the loss of TDP-43 using the new pipeline. As a result, we identified 66 novel cryptic splicing events in addition to STMN2 cryptic exon. Interestingly, the UNC13A cryptic splicing event is one of the most significant (Figure 2) (12). Thus, we immediately paid attention to the UNC13A gene since it is one of the top hits for ALS/FTD in the genome-wide association studies (15), (16).

Without nuclear TDP-43, a cryptic exon of 128 bp is included in UNC13A mRNA, which introduces a premature stop codon. TDP-43 binding sites in the intron harbored this cryptic exon, suggesting that TDP-43 directly regulates this splicing event. We analyzed a series of postmortem samples from the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank and the New York Genome Center and found the inclusion of the novel UNC13A cryptic exon in the brains of FTLD-TDP and ALS patients (12). At the same time, another team also identified the cryptic exon inclusion in UNC13A due to TDP-43 depletion. They found this cryptic exon by detailed analysis of RNA sequencing from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS)-derived neurons depleted for TDP-43 (13). Thus, both teams have demonstrated the cryptic splicing event in the UNC13A gene by TDP-43 dysfunction. This cryptic splicing event decreases normal UNC13A mRNA and protein since the abnormal UNC13A mRNA containing cryptic exon is degraded by nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), the mechanism to maintain protein quality (13). UNC13A encodes a critical neuronal protein essential for neurotransmitter release in the synaptic vesicles (17), (18). Therefore, the cryptic exon inclusion event in UNC13A could cause neuronal dysfunction in ALS/FTD pathogenesis.

UNC13A is one of the remarkable genetic risk factors for ALS and FTD, but it remains unclear how genetic variants, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), in the UNC13A gene increase the risk for the diseases. Notably, the two risk SNPs in UNC13A are located around the cryptic exon (12), (13), indicating the strong connection between the SNPs, risk for ALS/FTD, and the inclusion of cryptic exon. Figuring out how GWAS hits connect to disease pathogenesis has been a challenge. However, connecting genetics to pathology, both groups found that human brain samples derived from ALS/FTD patients harboring the risk alleles for these two GWAS SNPs have more UNC13A cryptic exon inclusion than those without risk alleles (12), (13). These SNPs are insufficient to cause cryptic exon splicing on their own since we did not detect them in the RNA sequencing data of healthy control samples with risk alleles (12). Instead, this genetic vulnerability is likely TDP-43-loss dependent, not causing pathogenesis until TDP-43 becomes dysfunctional.

UNC13A cryptic exons are abundant in the brains of patient with ALS and FTD, and the risk of SNPs in the gene potentiates the accumulation of these cryptic exons. Indeed, patients with one copy of the risk SNPs live shorter than those with zero, and those with two copies of the risk SNPs live even shorter (12). This fact is consistent with previous analyses indicating decreased survival in patients with ALS and FTD harboring UNC13A variants (19). Thus, since genetic variants in UNC13A that increase cryptic exon inclusion are associated with decreased patient survival, we speculate that therapeutic strategies to block this splicing event could have a partial therapeutic benefit. Discovering a novel TDP-43-dependent cryptic splicing event in ALS/FTD risk gene opened new provocative directions for validating UNC13A as a biomarker. Although we should think that this might be just a part of the whole, we now have a sensitive way of detecting the cellular consequences of TDP-43 loss of function, even before TDP-43 nuclear depletion and cytoplasmic aggregation appear. Our method will allow a more sensitive study of ALS and FTD mechanisms and pathology in brain tissues derived from patients.

TDP-43 belongs to the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) family, which essentially functions to regulate multiple aspects of RNA metabolism (20). Similar to TDP-43, other hnRNPs (C, K, L, M, PTBP1) are known to suppress cryptic exon inclusion (21), (22), (23), (24), (25), (26). Several hnRNPs have been identified as regulators of the alternative splicing events of sortilin1, one of the TDP-43 targeting genes (24). It suggests that many proteins working in the connection within a network are critical for regulating the alternative splicing targeted by TDP-43. Therefore, this study aimed to further investigate the role of TDP-43 and other hnRNPs in regulating UNC13A cryptic splicing (27). The findings revealed that hnRNP L, hnRNP A1, and hnRNP A2B1 bind UNC13A RNA and regulate its cryptic splicing event. Higher levels of hnRNP L are associated with lower levels of UNC13A cryptic RNA in FTLD-TDP cases. Furthermore, when TDP-43 protein levels are depleted, hnRNP L can reduce UNC13A cryptic exon inclusions (27). We indicated that other hnRNPs, particularly hnRNP L, can regulate UNC13A splicing under loss of TDP-43 function, working as a potential disease modifier.

Interestingly, TDP-43 regulates the splicing of its own TARDBP mRNA, encoding TDP-43, similar to other target genes. It has been found that TDP-43 strictly autoregulates the expression levels of TDP-43 in the nucleus by regulating alternative splicing in TARDBP mRNA as follows: In healthy status, TDP-43 binds the TARDBP pre-mRNA 3′UTR in the nucleus and regulates its alternative splicing (28), (29), (30). An increased level of nuclear TDP-43 results in its alternative splicing to induce the variants, which are sensitive to NMD, to reduce TDP-43 levels. Conversely, when the level of TDP-43 in the nucleus decreases, the TARDBP mRNA levels increase following the reduction of its alternative splicing. Therefore, TARDBP mRNA expression levels continually increase in ALS-affected cells with reduced nuclear TDP-43 levels (30). The formation of cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregates is estimated to enhance the depletion of the TDP-43 level in the nucleus (31). Consequently, cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregates cause the disease progression via the perturbation of these autoregulatory mechanisms (32).

The aberrant splicing events containing cryptic exon inclusion can be considered potential biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and evaluation of the efficacy of therapeutics (Figure 1) (8). Several candidate fluid biomarkers have been known, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (33) and neurofilament light chain protein (34). However, these markers reflect nonspecific neurodegeneration rather than specific pathogenesis of ALS/FTD. The next step is to evaluate these novel TDP-43-dependent abnormal splicing events and validate them in the biofluids derived from ALS and FTD patients. Since some of the cryptic exon splicing events result in the production of cryptic peptides, the levels of these peptides reflect the loss of TDP-43 function in the affected brains. Monitoring the levels of cryptic peptides in the samples derived from patients is one of the biggest challenges in the ALS and FTD field. Even though the STMN2 cryptic exon is highly abundant in the central nervous systems (9), (10), (11), detecting the cryptic peptide from truncated STMN2 has remained elusive. UNC13A and other cryptic peptides cannot be translated, owing to NMD, or are cleared immediately and thus impossible to detect (8). They may be low or not released outside the affected cells even if translated. Moreover, the success of the biomarker for cryptic peptides depends on the ability to create high-quality and specific antibodies. In this context, two independent research groups have recently demonstrated that, for some TDP-43 target splicing events translated in-frame manner, abnormal peptides from abnormal splicing variants, including cryptic exons, can be detected in human cerebrospinal fluid (35), (36). Therefore, we strongly suspect that the field will unveil new facets of ALS and FTD pathology once it develops suitable tools to detect the series of aberrant splicing events.

The emergence of aberrant splicing events as a disease mechanism in ALS/FTD opens up many exciting possibilities for robust novel biomarkers. One challenge may be to determine which of these dozens of new TDP‐43 splicing targets contribute to ALS/FTD. Supposing many splicing events contribute to disease simultaneously, targeting them one by one should be very difficult, and other radical approaches focused on improving the TDP-43 function itself might be needed. Indeed, there are strong connections between UNC13A, the cryptic exon inclusion event, and human genetics, letting us focus on UNC13A as a marker reflecting the pathophysiology. Nevertheless, it is essential to further investigate other candidate genes involved in the ALS/FTD pathogenesis.

This article is based on the study, which received the Medical Research Encouragement Prize of The Japan Medical Association in 2023.

None

YK contributed to the search of previous publications and wrote the whole manuscript.

Taylor JP, Brown RH, Jr, Cleveland DW. Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature. 2016;539(7628):197-206.

Ling SC, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron. 2013;79(3):416-38.

Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130-3.

Arai T, Hasegawa M, Akiyama H, et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351(3):602-11.

Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(R1):R46-64.

Sun M, Bell W, LaClair KD, et al. Cryptic exon incorporation occurs in Alzheimer's brain lacking TDP-43 inclusion but exhibiting nuclear clearance of TDP-43. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133(6):923-31.

Ling JP, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, et al. TDP-43 repression of nonconserved cryptic exons is compromised in ALS-FTD. Science. 2015;349(6248):650-5.

Akiyama T, Koike Y, Petrucelli L, et al. Cracking the cryptic code in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: towards therapeutic targets and biomarkers. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(5):e818.

Melamed Z, López-Erauskin J, Baughn MW, et al. Premature polyadenylation-mediated loss of stathmin-2 is a hallmark of TDP-43-dependent neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(2):180-90.

Klim JR, Williams LA, Limone F, et al. ALS-implicated protein TDP-43 sustains levels of STMN2, a mediator of motor neuron growth and repair. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(2):167-79.

Prudencio M, Humphrey J, Pickles S, et al. Truncated stathmin-2 is a marker of TDP-43 pathology in frontotemporal dementia. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):6080-92.

Ma XR, Prudencio M, Koike Y, et al. TDP-43 represses cryptic exon inclusion in the FTD-ALS gene UNC13A. Nature. 2022;603(7899):124-30.

Brown AL, Wilkins OG, Keuss MJ, et al. TDP-43 loss and ALS-risk SNPs drive mis-splicing and depletion of UNC13A. Nature. 2022;603(7899):131-7.

Liu EY, Russ J, Cali CP, et al. Loss of nuclear TDP-43 is associated with decondensation of LINE retrotransposons. Cell Rep. 2019;27(5):1409-21.e6.

Diekstra FP, Van Deerlin VM, van Swieten JC, et al. C9orf72 and UNC13A are shared risk loci for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a genome-wide meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(1):120-33.

van Es MA, Veldink JH, Saris CG, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 19p13.3 (UNC13A) and 9p21.2 as susceptibility loci for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1083-7.

Augustin I, Rosenmund C, Südhof TC, et al. Munc13-1 is essential for fusion competence of glutamatergic synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1999;400(6743):457-61.

Böhme MA, Beis C, Reddy-Alla S, et al. Active zone scaffolds differentially accumulate Unc13 isoforms to tune Ca(2+) channel-vesicle coupling. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(10):1311-20.

Tan HHG, Westeneng HJ, van der Burgh HK, et al. The distinct traits of the UNC13A polymorphism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(4):796-806.

Bampton A, Gittings LM, Fratta P, et al. The role of hnRNPs in frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(5):599-623.

Ling JP, Chhabra R, Merran JD, et al. PTBP1 and PTBP2 repress nonconserved cryptic exons. Cell Rep. 2016;17(1):104-13.

McClory SP, Lynch KW, Ling JP. HnRNP L represses cryptic exons. RNA. 2018;24(6):761-8.

Bampton A, Gatt A, Humphrey J, et al. HnRNP K mislocalisation is a novel protein pathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and ageing and leads to cryptic splicing. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;142(4):609-27.

Mohagheghi F, Prudencio M, Stuani C, et al. TDP-43 functions within a network of hnRNP proteins to inhibit the production of a truncated human SORT1 receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(3):534-45.

West KO, Scott HM, Torres-Odio S, et al. The splicing factor hnRNP M is a critical regulator of innate immune gene expression in macrophages. Cell Rep. 2019;29(6):1594-609.e5.

Zarnack K, König J, Tajnik M, et al. Direct competition between hnRNP C and U2AF65 protects the transcriptome from the exonization of Alu elements. Cell. 2013;152(3):453-66.

Koike Y, Pickles S, Estades Ayuso V, et al. TDP-43 and other hnRNPs regulate cryptic exon inclusion of a key ALS/FTD risk gene, UNC13A. PLOS Biol. 2023;21(3):e3002028.

Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, et al. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(4):459-68.

Ayala YM, De Conti L, Avendaño-Vázquez SE, et al. TDP-43 regulates its mRNA levels through a negative feedback loop. EMBO J. 2011;30(2):277-88.

Koyama A, Sugai A, Kato T, et al. Increased cytoplasmic TARDBP mRNA in affected spinal motor neurons in ALS caused by abnormal autoregulation of TDP-43. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(12):5820-36.

Sugai A, Kato T, Koyama A, et al. Robustness and vulnerability of the autoregulatory system that maintains nuclear TDP-43 levels: A trade-off hypothesis for ALS pathology based on in silico data. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:28.

Sugai A, Kato T, Koyama A, et al. Non-genetically modified models exhibit TARDBP mRNA increase due to perturbed TDP-43 autoregulation. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;130:104534.

Gao L, Zhou S, Cai H, et al. VEGF levels in CSF and serum in mild ALS patients. J Neurol Sci. 2014;346(1-2):216-20.

Verde F, Otto M, Silani V. Neurofilament light chain as biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:679199.

Seddighi S, Qi YA, Brown AL, et al. Mis-spliced transcripts generate de novo proteins in TDP-43-related ALS/FTD. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(734):eadg7162.

Irwin KE, Jasin P, Braunstein KE, et al. A fluid biomarker reveals loss of TDP-43 splicing repression in presymptomatic ALS-FTD. Nat Med. 2024;30(2):382-93.