Corresponding author: Junya Tsurukiri, junya99@tokyo-med.ac.jp

DOI: 10.31662/jmaj.2021-0108

Received: June 8, 2021

Accepted: September 21, 2021

Advance Publication: December 28, 2021

Published: January 17, 2022

Cite this article as:

Kato T, Tsurukiri J, Sano H, Nagura T, Moriya M, Suenaga H, Matsunaga K, Kanemura T, Ueta Y, Arai T. Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus Caused by Cerebrospinal Fluid Dissemination of a Salivary Duct Carcinoma: A Case Report. JMA J. 2022;5(1):151-156.

Salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) is a rare and highly aggressive salivary gland tumor with rapid growth, distant metastasis, and a high recurrence rate. Moreover, the parotid gland is the most common site with a poor prognosis. A lower frequency of distance metastasis to the liver, skin, and brain has also been reported, although the lungs, bones, and lymph nodes are the most common sites of SDC metastasis. We report a case of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) in a 73-year-old male comatose patient having SDC of the parotid gland with an unusual metastasis to the skin and brain diagnosed by frequent cerebrospinal fluid examinations. Meningeal carcinomatosis usually has a poor prognosis, and NCSE is a reversible cause of altered mentation. Clinicians should know the unique set of epilepsy etiologies in patients with malignant tumors.

Key words: epilepsy, nonconvulsive status epilepticus, malignant tumor, disturbance of consciousness, salivary duct carcinoma

Salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) is a rare salivary gland tumor that occurs in the ductal epithelium of the salivary gland, is often difficult to treat, and is associated with poor outcomes (1). Pulmonary and bone metastases are common, whereas skin and central nervous system (CNS) metastases are uncommon (2). We treated a patient presenting with disturbance of consciousness (DOC) caused by nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), who developed SDC and metastases to the meninges.

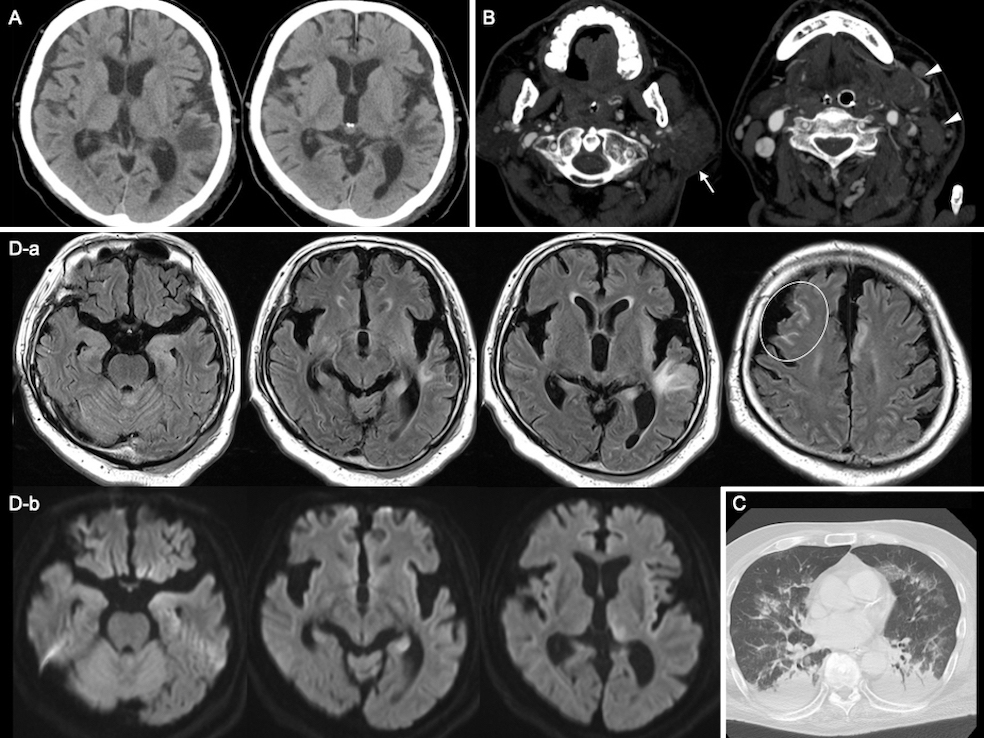

A 73-year-old male was transferred to our emergency center because of DOC with no remarkable past medical history. His physical examination revealed the following: Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, E1V1M1; pupil diameter, 2 mm; blood pressure, 106/78 mmHg; heart rate, 150 beats/min; respiratory rate, 28 breaths/min; and body temperature, 36.6°C. We observed muscle twitching in the upper limbs and face, and bedsores of the buttock, tendon reflexes were normal, and the Babinski sign was indifferent. We also observed a well-defined elastic solid mass (48 × 31 mm) in the left submandibular triangle and multiple infiltrative solid elastic red plaques/nodules in the left chest. His laboratory examinations are listed in Table 1. Computed tomography (CT) of the head revealed a low-density area in the left temporal lobe suspected to be edematous. Cervical CT imaging showed lymphadenopathy of the left neck and a continuous mass in the left parotid gland. Chest CT imaging showed pneumonia (Figure 1A, B and C).

Table 1. Laboratory Test and Cerebrospinal Fluid Examination on Arrival at Our Emergency Department.

| Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory tests | Reference range | |||

| White blood cells | 6,610 | /µL | 3,600–9,000 | /µL |

| Red blood cells | 501 | /µL | 387−525 | /µL |

| Hemoglobin | 15.9 | g/dL | 12.6–16.5 | g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 49 | % | 37.4−48.6 | % |

| Platelet | 14.6 | /µL | 13.8−30.9 | /µL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 108 | U/L | 30 | U/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 39 | U/L | 30 | U/L |

| Creatine kinase | 3077 | U/L | 60−287 | U/L |

| Urea nitrogen | 50.9 | mg/dL | 7−24 | mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 2.54 | mg/dL | 1.00 | mg/dL |

| Sodium | 146 | mg/dL | 135−147 | mg/dL |

| Potassium | 4.2 | mg/dL | 3.3−4.8 | mg/dL |

| Chloride | 105 | mg/dL | 98−108 | mg/dL |

| Glucose | 97 | mg/dL | 78−109 | mg/dL |

| Ammonia | 22 | µg/dL | 30−80 | µg/dL |

| C reactive protein | 38.59 | mg/dL | 0.3 | mg/dL |

| Prothrombin-international normalized ratio | 1.21 | 0.9−1.1 | ||

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | 35.4 | sec | 27−40 | sec |

| D-dimer | 29.3 | µg/dL | 1.0 | µg/dL |

| Cerebrospinal fluid examination | ||||

| Pressure | 240 | mmHg | 50−80 | mmHg |

| Quantitative protein | 63 | mg/dL | 15−40 | mmHg |

| Quantitative glucose | 46 | mg/dL | 45–80 | mg/dL |

| Cell count | 2 | /uL | < 5 | /uL |

| Bacterial culture | negative | |||

| Herpes smplex virus DNA | negative | |||

| Varicella zoster virus DNA | negative | |||

| DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid | ||||

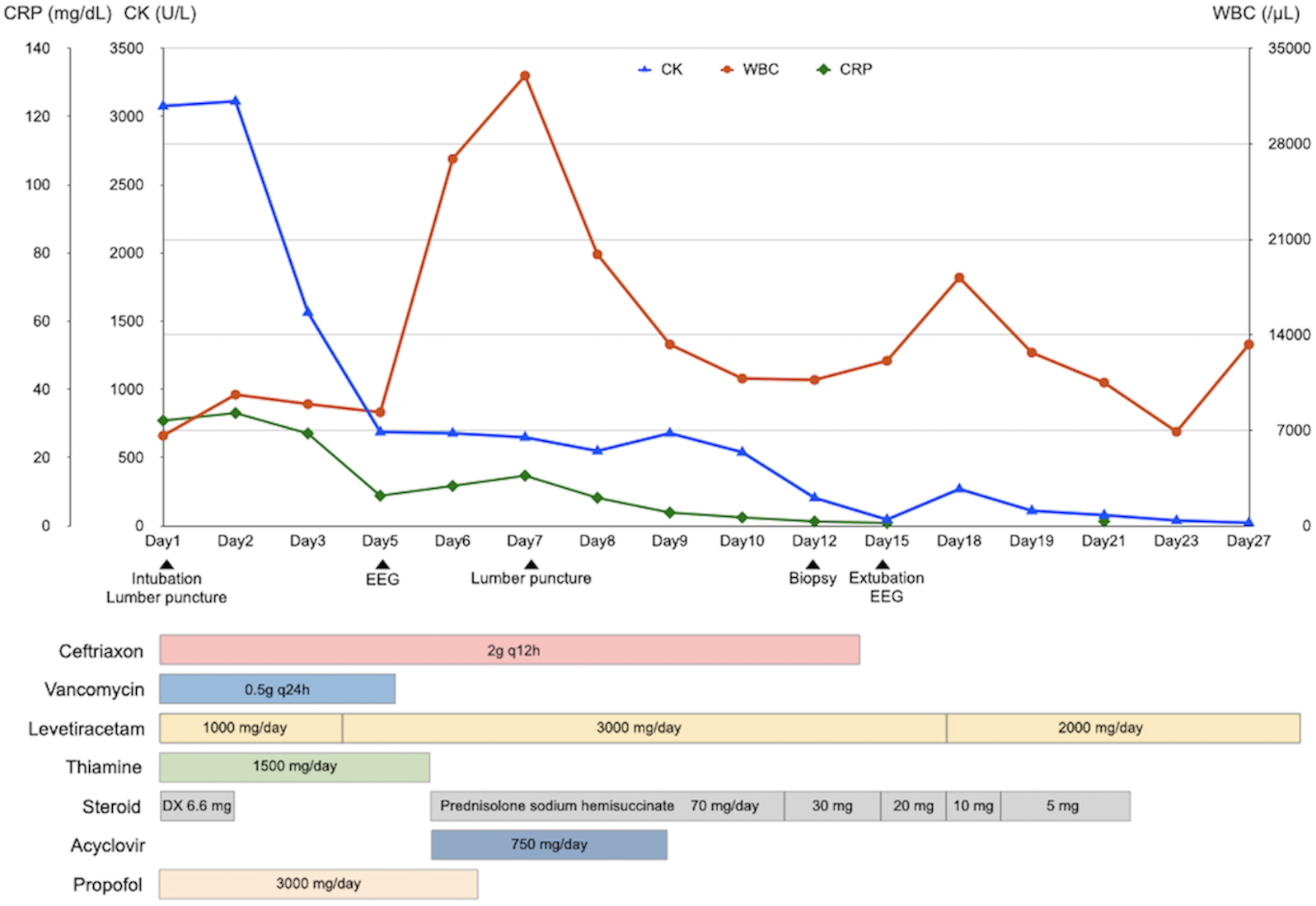

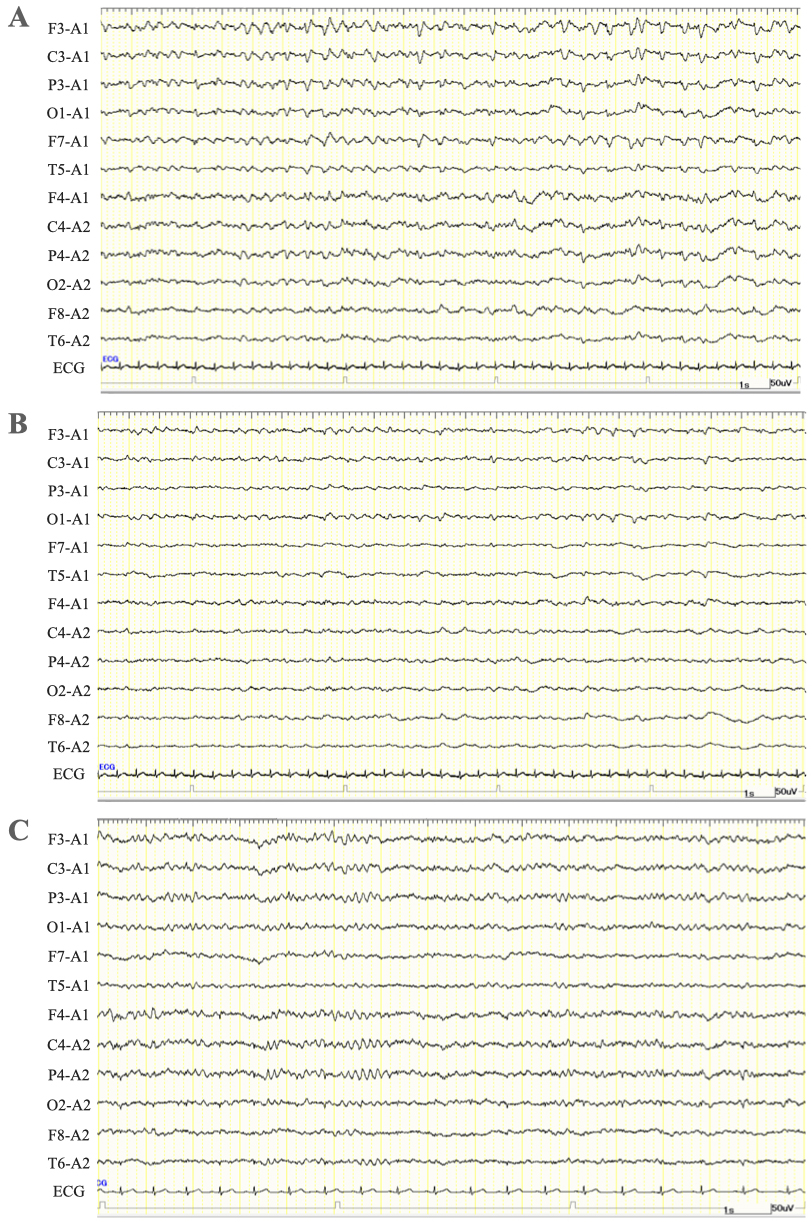

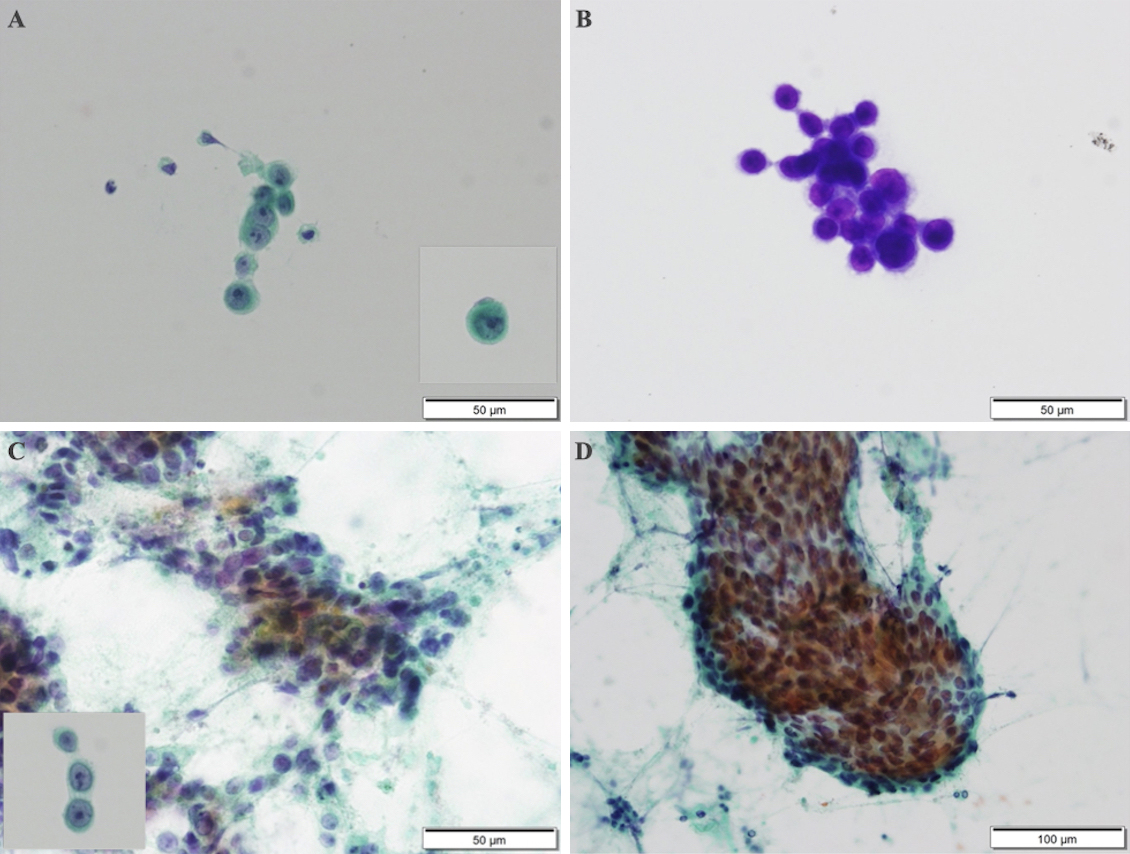

The patient was diagnosed with sepsis and required mechanical ventilation and critical care management under anesthesia. His clinical course is shown in Figure 2. NCSE, bacterial meningitis, or Wernicke’s encephalopathy was also suspected, and levetiracetam (1000 mg/day), vitamin B1, and intravenous steroids were initially administered. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed abnormal intensity in both cerebral hemispheres, suggesting NCSE or limbic encephalitis, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging revealed high intensity in the subarachnoid space, suggesting meningeal carcinomatosis (Figure 1D). Electroencephalography (EEG) showed lateralized rhythmic delta activity (LRDA) and lateralized periodic discharges (LPDs) with triphasic morphology predominantly in the left frontal parietal region fluctuating in frequency and morphology (Figure 3A, B) (3). CSF cytology showed large lymphocyte-like cells with prominent nucleoli, which was a Class V malignant tumor on day 7 (Figure 4A, B). His consciousness improved to GCS E4VtM5, and the patient was extubated. On day 12, a skin biopsy of the left chest skin eruption revealed metastatic skin cancer. Furthermore, the left cervical lymph node was biopsied and revealed a Class V SDC (Figure 4C, D). The clinical diagnosis of NCSE caused by meningeal carcinomatosis was posed, and a repeat EEG on day 15 revealed disappearance of LRDA (Figure 3C). The patient was discharged from the hospital to another hospital after 37 days.

SDC increases in neck masses or facial nerve paralysis are likely to become symptomatic (4). Metastases to distant organs occur in 40%-70% of adult patients, with pulmonary, bone, and lymph node metastases being the most common, whereas liver, skin, and CNS are less common (2). Although the standard treatment for SDC is radical surgery, the recurrence rate is high(2), (5). Past studies reveal skin and brain metastases in one patient requiring long-term follow-up even after remission (6).

Meningeal carcinomatosis is a disease associated with poor prognoses, presenting with meningeal dissemination in which cancer cells float in the CSF and proliferate diffusely in the pia mater of the brain and subarachnoid space (7). In this patient, CSF tests conducted by several lumbar punctures for the differential diagnosis of DOC showed increased CSF pressure and quantitative protein, and cytology revealed meningeal carcinomatosis of the SDC. Furthermore, on the basis of the original EEG findings and a positive electroclinical response to antiepileptic therapy, we diagnosed NCSE due to meningeal carcinomatosis.

The etiologies of NCSE are poor compliance to medications, alcohol intoxication, infection, stroke, CNS tumors, or trauma (8). NCSE occurs in 6%-8% of patients with cancer, and it can be the presenting sign of a new brain disorder or metastasis (9). NCSE is a likely cause of altered mental status in patients with encephalopathy without organ failure. Therefore, early administration of antiepileptic drugs should be a priority (10).

In conclusion, NCSE can be a reversible cause of altered mentation, although meningeal carcinomatosis is associated with a poor prognosis. Clinicians should be aware of the unique set of NCSE etiologies in patients with rare malignant tumors, and once these are identified, consideration of a rapid multidisciplinary diagnostic approach is essential for making decisions regarding the appropriate treatment.

None

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hirano Hiroshi and Dr. Wakiya Midori (Pathology department of Tokyo Medical University Hachioji Medical Center) for their pathological diagnosis, and Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Conceived and designed the experiments: KT, TJ

Contributed to interpretation of data: SH, MK, NT, MM, SH, KT

Approved the final version to be submitted: UY, AT

Written informed consent was obtained from the next of kin of the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Gilbert MR, Sharma A, Schmitt NC, et al. A 20-year review of 75 cases of salivary duct carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142(5):489-95.

Otsuka K, Imanishi Y, Tada Y, et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors for salivary duct carcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis of 141 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(6):2038-45.

Trinka E, Leitinger M. Which EEG patterns in coma are nonconvulsive status epilepticus? Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:203-22.

Stodulski D, Mikaszewski B, Majewska H, et al. Parotid salivary duct carcinoma: a single institution’s 20-year experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(7):2031-8.

Han MW, Roh JL, Choi SH, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome analysis of salivary duct carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2015;42(6):472-7.

Sadeghi HM, Karimi A, Rahpeima A, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma with late distant brain and cutaneous metastasis: a case report. Iran J Pathol. 2020;15(3):521-5.

Lombardi G, Zustovich F, Farina P, et al. Neoplastic meningitis from solid tumors: new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Oncologist. 2011;16(8):1175-88.

Grewal J, Grewal HK, Forman AD. Seizures and epilepsy in cancer: etiologies, evaluation, and management. Curr Oncol Rep. 2008;10(1):63-71.

Wang N, Bertalan MS, Brastianos PK. Leptomeningeal metastasis from systemic cancer: review and update on management. Cancer. 2018;124(1):21-35.

Gutierrez C, Chen M, Feng L, et al. Non-convulsive seizures in the encephalopathic critically ill cancer patient does not necessarily portend a poor prognosis. J Intensive Care. 2019;7:62.